Illustrated by Vishaka Kalingeri Rao on Canva

Advocacy in the digital age

From #MeToo to the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement - understanding digital spaces as a catalyst for activism and advocacy.

Activism and advocacy are integral aspects of our life – it is the through which we can connect with our identities, seek justice and create change. It has been foundational in the creation of nations and institutions.

In the 21st century, advocacy and activism have transformed rapidly along with technological developments. The biggest being the creation of the internet and the integration of digital spaces in our lives. As a result, this space has taken on an important role in facilitating organization for activism and advocacy,y either through social networking channels or as platforms for the dissemination of information.

In addition to social networking sites, the online space has created tools with the sole purpose of advocating. Websites such as Jhatkaa in India and GetUp! In Australia have successfully petitioned to create real institutional changes (Hall & Ireland, n.d.). These organizations act as digital non-profits with wider reach and the ability to rapidly represent a variety of issues at the same time.

In this project, we will be examining the phenomenon of digital advocacy through two case studies. The first represents a stable organizational form of advocacy, which primarily promotes different causes and education through the social media infographic format. The second case study examines user-based activism using different social media platforms. Additionally, it allows us to analyze how digital activism can transcend cultural and linguistic barriers as it spreads across countries.

Contextualizing Digital Advocacy

Our digital lives have become immensely intertwined with our social lives to an extent where it is often challenging to separate the processes that constitute “online” vs “offline.” This phenomenon is embodied by the term “techno-social life” introduced by Dr. Mary Chayko, a distinguished teaching professor of Communication and Information (2022). It highlights the idea that with our continued use of digital technology, there is a greater enmeshing of the “real” and the “virtual.” If this is true for aspects of our life, such as general socializing it is true for the process of activism.

Transformation of activism in the digital space has significantly impacted the way the internet and digital technology have been used for this purpose. The term “techno-politics” captures the “nexus” between technology and politics (Gerbaudo, 2017). The history of digital activism and attitudes towards it can be classified by the 2 major evolutions of the digital world – Web 1.0 and Web 2.0. These “techno-political” orientations were impacted by factors such as, but not limited to, accessibility to technology and political and cultural shifts happening in the offline world. Paulo Gerbaudo, an Italian sociologist and political theorists, who is the Director of the Centre for Digital Culture at King’s College in London, notes a shift in activism and politics online from web 1.0 which was period where technological affordances were not as widespread, compared to web 2.0 which was the period of bringing technology to the masses, with the innovation of social media (2017).

In this project, we will be exploring how techno-politics in the era of Web 2.0 has led to two distinct forms of activism online. The first which creates a new form called “information activism” (Dumitrica & Hockin-Boyers, 2023). Its main objective is to raise awareness by capturing engagement on social media platforms through infographics. Often, this form of activism uses digital technology as a tool to spread awareness about a particular or multitude of causes (s). For the purpose of this project, we will be studying the non-profit Dear Asian Youth as a case study.

On the other hand, there are movements which have been fostered online. Their start can be traced to communities and online forums which gain traction. As a result, they have incredible impacts on the socio-political climate and seep into the mainstream. An example of this form is the radical feminist 4B movement in South Korea. As we explore these case studies and techno-politics, the main question to consider is related to techno-determinism. Is the success of digital advocacy due to the affordance of technology, or is it the users who enact their agency to use it as a tool for their causes?

Rise of the Information Activist - Podcast interview with Dear Asian Youth

Dear Asian Youth defines itself as "By Asian youth, for Asian youth (LinkedIn). It is an international non for profit organization dedicated towards unifying Asian Youth through intersectional education.

Their educational content is shared on their social media platforms, such as Instagram, where they make use of what has come to be known as the "social media infographic" format. According to Dr. Delia Dumitrica, an expert in the field of Media and Communication with a specialisation in political communications, this format is also known as "slideshow activism" (2022). It consists of easily accessible and digestible text along with impactful images.

A Creator's perspective -slide show activism, engagement and predictions for the future

The 4B movement is a radical feminist movement that was started in South Korea as a form of resistance against the long history of inequal treatment between men and women and rise of crimes against women

The term 4B refers to the four main forms of protest that women engage in as a part of this movement. It encompasses bihon – no marriage, bichulsan – no childbirth, biyonae – no dating and bisekseu – no sex (Lee & Jeong, 2021).

It is important to note that these apply in a heterosexual context and not much is described concerning other sexualities. The prefix bi (pronounced bee) is derived from the Chinese character denoting “not.”

The movement has been approximated to have emerged in 2015 on social networking sites such as Twitter (now X). Digital feminists have participated in this movement as is a counter movement to changing societal expectation placed on women in South Korea. It encourages women to redefine marriage and childbirth as a political act (Lee & Jeong, 2021).

The 4B movement started off through social media discourse with Korean women expressing dissent against the institutions that placed gendered societal pressures on women in addition to the high stress and competitive experience of schooling and the job market in South Korea (Lee & Jeong, 2021). The movement mainly gained prevalence on social media websites like Twitter (now X). Later digital feminist efforts were consolidated under the group called “Megalian,” which is now defunct but made a major impact on Korean society.

Recent attacks on women’s rights such as the overturning of Roe v Wade failure to protect safe abortion laws has left women exasperated. Content and searches about the 4B movement spiked following the recent Presidential election (Cherelus, 2024). However, due to normative differences between the global west and the east – the scope of this movement in the US is unpredictable now. However, it is important to note that crucial role of the digital medium as information dissemination primarily happened through platforms such as X (formerly Twitter) and TikTok.

What is the 4B Movement?

Investigating the phenomenon of 4B and other comparable movements, such as the #MeToo movement, we found that they have grown digitally and are based on individual action. However, their ability to produce real-life consequences reinforces the idea of enmeshment between the real and the digital—technopolitics. Individual action in digital activism is self-motivating and self-produced (Mirbabaie et al., 2021).

Traditional companies and organizing agents do not play a major role. The 4B movement is a form of “connective action” (Mirbabaie et al., 2021) where participating in movements is mediated by digital social networks and is founded in a cycle of producing and sharing content. The lack of traditional forms of organizers can give rise to new forms of institutions that appropriate the roles of traditional organizers, such as the case of Megalian. Digital Activism that has its origins rooted online tends to focus more on anecdotes to connect to the larger issue, rather than the converse with information activism, where the larger issue is highlighted first. The success of this form of digital activism is unpredictable and based on other factors. It might be easy to have an issue with trending, but maintaining its longevity is not easy (Menon, n.d.).

Image Credit: Jung Yeon-je / AFP

Source: Free Malaysia Today

Moving Forward : Digital Advocacy in the Future

Rapid communication and a broader reach are making digital spaces a mainstay for activism moving forward. Whether it is through messaging services, social media campaigning or online petitions, digital spaces and activism are already deeply intertwined, and it is likely to continue. By the year 2050, it is possible that we won’t be able to separate the online and offline components of activism, similar to how our understanding of communication and socialization has become augmented. Digital tools provide a broader repertoire of politically oriented actions, pushing the boundaries of what comprises activism (Dumitrica & Hockin-Boyers, 2023). The Instagram slideshow format has changed the methodology for spreading awareness and campaigning, giving birth to a new form of activism called “Information activist”(Dumitrica & Hockin-Boyers, 2023) and connective action (Mirbabaie et al., 2021).

Challenges to Digital Activism

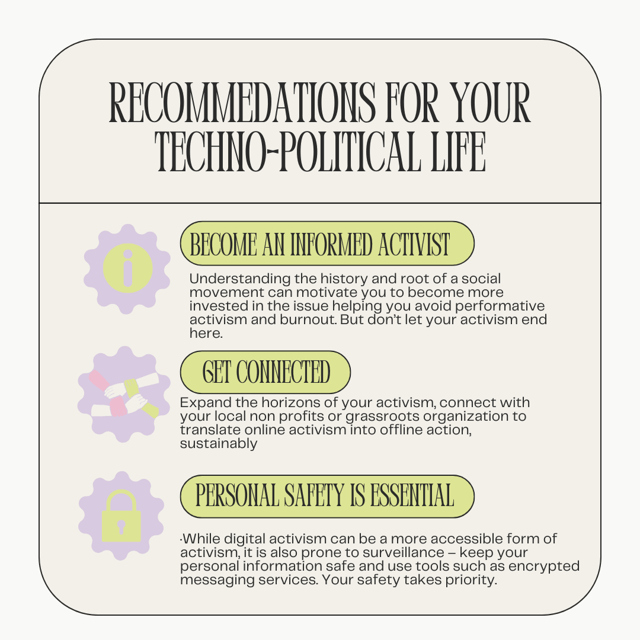

The challenges to digital activism can be categorized under two main issues: longevity and performativity. Understanding these two factors can greatly help us predict the success of the movement. Capturing the attention of audiences is important, but keeping up the momentum of the movement to manifest outside of the space. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) acknowledges the power of digital activism but emphasizes that there needs to be a sustainable network and institutions established as a form of follow-through (Vince, 2024). This is especially true of activism that falls under the label of connective action. When all aspects of activism are rooted only in individual action, there is a major risk of burnout.

Additionally, another potential challenge to both information activism and connective action is performativity. Performativity in this context refers to “empty activism”, where the main objective is self-serving (Jackson & Eaton, 2024). For both individuals and corporations, it reflects the tendency to want to seem to have socially desirable traits. It directly influences the longevity of a movement,t as performative action is likely the quickest to burn out. Previously, digital activism has been especially riddled with performativity, creating neologisms such as “slacktivism” (Fisher, 2020). However, making a blanket statement that all forms of digital activism are lazy is an oversimplification. Some of the most significant movements of the 21st century have had a strong digital presence, ranging from #BlackLivesMatter to #MeToo (Fisher, 2020).

Predicting the Future: Techno-politics is here to stay

Rahib Imamguluyev's insightful article on AI predictions in the year 2050 highlights how the relationship between humans and technology will become more collaborative. He predicts that AI technology would become “digital companions” (2024, p. 2935). Similarly, the digital counterpart of activism is likely to become a key component of activism moving forward. To the extent that traditional means of organizing might feel incomplete without the digital aspect.

As affordances of digital technologies continue to facilitate newer forms of activism, there is also a rise in concerns over true impact and surveillance. Especially with social media spaces taking on a more political role with activism, it could lead to increased surveillance from institutions (Uldam, 2018). While this issue is still in its nascent stages, the combination the individual visibility with the expression of politics can leave users in a vulnerable state. Imamguluyev predicts a similar challenge for the development of AI. Technology can facilitate surveillance by corporate and government institutions. He calls for “robust cybersecurity measures” (2024). In the case of digital activism, along with cybersecurity, there is a need for the expansion of dissenting rights and privacy rights to digital spaces.

Bibliography

Chayko, M. (2022). Living and Connecting in the Digital Age.

Cherelus, G. (2024, November 8). After the Election, a Call for Women to Swear Off Men. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/08/style/4b-movement.html

Dumitrica, D., & and Hockin-Boyers, H. (2023). Slideshow activism on Instagram: Constructing the political activist subject. Information, Communication & Society, 26(16), 3318–3336. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2155487

Dumitrica, D., & Hockin-Boyers, H. (2023). Slideshow activism on Instagram: Constructing the political activist subject. Information, Communication & Society, 26(16), 3318–3336. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2155487

Fisher. (2020, September 16). The subtle ways that ‘clicktivism’ shapes the world. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200915-the-subtle-ways-that-clicktivism-shapes-the-world

Gerbaudo, P. (2017). From cyber-autonomism to cyber-populism: An ideological history of digital activism. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 15(2), 477–489.

Imamguluyev, R. (2024). Artificial Intelligence 2050: Predictions, Challenges, and Innovations. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 5, 2933–2941. https://doi.org/10.55248/gengpi.5.0924.2663

Jackson, S. C., & Eaton, A. A. (2024). Stop the Show: A Call to End Performative Activism. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 36(3), 159–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/19394225241279581

Lee, J., & and Jeong, E. (2021). The 4B movement: Envisioning a feminist future with/in a non-reproductive future in Korea. Journal of Gender Studies, 30(5), 633–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.1929097

Lee, J., & Jeong, E. (2021). The 4B movement: Envisioning a feminist future with/in a non-reproductive future in Korea. Journal of Gender Studies, 30(5), 633–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.1929097

Menon, A. (n.d.). Activism on Twitter: Effectiveness & Effects on Real-Time Policies. TIPSCON 2020, 165.

Mirbabaie, M., Brünker, F., Wischnewski, M., & Meinert, J. (2021). The development of connective action during social movements on social media. ACM Transactions on Social Computing, 4(1), 1–21.

Uldam, J. (2018). Social media visibility: Challenges to activism. Media, Culture & Society, 40(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717704997

Vince. (2024, December 13). Gen Z’s Next Challenge: Transforming Activism Into Lasting Change | NAACP. https://naacp.org/articles/gen-zs-next-challenge-transforming-activism-lasting-change